Toward the beginning of Pierre Bourdieu’s newly published 1999-2000 lectures from the College de France (Manet: A Symbolic Revolution), a perplexed art student asks Bourdieu the following question, one that the verbatim lectures show to have worried and preoccupied the great theorist of practice:

Your recent conferences have astonished me. For when you speak of developing a theoretical approach to art, taking note not of the intentions of the artist but of his dispositions, this implies that the artist cannot be the author of a theoretical work, as Kandinsky was, because he cannot be conscious of the dispositions that he has acquired unconsciously. As an artist, I find this point of view difficult to accept, for I see in it a risk of alienation that is heavy with consequences and, in this case, must I conclude that I am unable to write a thesis? (Bourdieu 2017: 60)

This question comes after Bourdieu makes claims like the 19th century French artist Edouard Manet included “explosive” qualities in his work “without necessarily being aware of it” (27), that if we were to ask about any Manet painting “Did Manet consciously want to do that and did he premeditate what he put into that painting?” the answer must be an unambiguous “no” (45), and finally, as Bourdieu claims, “What I am describing here is … not the conscious mind of the painter … [but] a painter who finds himself practically engaged with the creation of his picture. He has, then, a practical intention, which is not at all his conscious, premeditated intention” (49-50). No wonder the student was perplexed.

The Manet that appears in Bourdieu’s lectures is not a great conversationalist and really has no unique insight into the nature of his craft. Truly as dumb as a painter, as the old saying goes. If, on a given day, you were to ask Manet “what are you doing?” he would very likely give a most honest reply: “I’m painting a picture.” As Bourdieu continues, “He might even have said a little more, for example: ‘I want to paint something that’ll be a work of art. I want to show that you can make something modern out of a classical model.’” Bourdieu believes that a similar boring answer would be given by Zola or [fill in the blank] writer of renown, or really any one of us as we engage in any activity (I am writing a blog post. I’m not quite sure what it is about. I believe something about Bourdieu). “But that does not make [Manet or Zola] or us either totally unconscious automata, or perfectly lucid subjects” (2017: 49).

What is so interesting about these lectures, and other of Bourdieu’s late work on art (1996), is that here we see the application of practice for the purposes of phenomenology, seeking a reconstruction of direct experience, but which I want to claim fits more the profile of a true heterophenomenology (Dennett 1991; 2003), which I’ll explain. Bourdieu wants to put himself and his readers in the artists’ shoes. He wants to know what it was like to be in the world from the “artist’s point of view,” confront the pragmata they confronted, their problems and their solutions for those problems, which he ultimately claims is the legacy they leave behind for other practitioners in a field to recapitulate (e.g. “Beethoven’s solution” or “Manet’s solution”). An opus infinitum, as Bourdieu confesses, and on several occasions in the lectures he admits his embarrassment at what does not know and never will. Yet there is merit in the task, as he explains, especially when the topic is art, or “pure practice without theory” (as Durkheim said).

Heterophenomenology is a coinage of the philosopher Daniel Dennett and my argument is that it is particularly useful for understanding exactly what Bourdieu is up to in this work, as a particularly relevant application of practice. As Dennett claims, heterophenomenology is, quite basically, the “phenomenology of another not oneself” (2003: 19). It is therefore a third-person accounting scheme (e.g. “Manet does”), but one that takes the “first person point of view [e.g. “I did”] as seriously as it can be taken.” What this means is that a heterophenomenologist (mouthful, hereafter HPist) understands that answers to to questions that, seemingly, give access to dimensions first-person experience (“What were you thinking when you painted X?”) are actually third-person investigations that invoke a person’s verbal capacity to link an internal state to a proposition (“I was thinking that …”). An HPist does not dismiss that kind of data, but neither does she take it at face value.

Rather, the job of the HPist is comprehensive. It involves generating a “fictional world … populated with all the images, events, sounds, smells, hunches, presentiments and feelings that the subject sincerely believes to exist in his or her (or its) stream of consciousness. Maximally extended, it is a neutral portrayal of exactly what it is like to be that subject” (Dennett 1991: 99).

The catch is that even though the HPist trusts the person, and “maintains a constructive and sympathetic neutrality” toward what people say about their experience and their action, this does not make those people the authority on the truth of the experience. What the world is like to them is at best an “uncertain guide” to what is going on for them as they experience and act. But neither does this mean that they are zombies (Dennett) or unconscious automata (Bourdieu). The point is that the HPist tries to compile a definitive description of the world according to subjects, but uses everything in that description as primary data, part of a “fictional world,” that is just the beginning of the analysis. It is what must be explained.

Dennett (2003) demonstrates what this using the following example from a famous experiment by Roger Shepard and Jacqueline Melzer (1971). Shepard and Melzer asked subjects whether the two drawings below (Figure 1) were of different objects or just different views of the same object. Nearly every subject reported that they solved the puzzle by rotating one of the figures in their “mind’s eye” to make a comparison. But were they really doing this mental rotation? If we were to ask a hundred people (including me!), they would probably all say that, yes, I mentally rotate the object on the right in order to answer that, indeed, these are two different views of the same object. The phenomenologist would be satisfied with this. The HPist, however, is more intrigued by “mental rotation” as a belief about conscious experience. She willfully submits that what this experience is like for subjects could have nothing to do with what is going on for subjects as they have this experience. But we first need to know that “mental rotation” is what the experience is like for them (see Pylyshyn 2002; Foglia and O’Regan 2016 for literature on mental imagery).

Figure 1

Dennett’s HPist strategy bears a none too faint resemblance to the method Bourdieu uses in answering the art student and in his remarkable analysis (68-72) of Manet’s painting Luncheon on the Grass (1863). Here, he attempts to put himself and his audience in Manet’s “historical place … a kind of imaginary reconstruction [of] Manet’s point of view as he was engaged in producing the Luncheon” (2017: 69). Thus, what Manet does here is basically create a tableau vivant, those still life paintings of groups of people arranged in some kind of scene that were so fashionable under Napoleon III. But he does something more than this. Bourdieu’s analysis is too detailed (even though he declares his shame about lacking the “necessary competence to do it”) to reproduce in its entirety. I’ll just point to two examples that resemble a heterophenomenology, ones that relate specifically to mental imagery.

First, Manet’s “symbolic revolution” is found in microcosm in the Luncheon because he had placed himself in an impossible situation in relation to his models: “he got [them] to adopt a classical pose, but through [their] clothing and his pictorial manner, he gave [them] modern connotations” (2017: 70). Did he intend to do this? Bourdieu says no. And to build that case he says that Manet effectively “pictured in his mind’s eye” a Venetian painting that he had seen at the Louvre (Marcantino Raimondi The Judgment of Paris … people in the bottom right corner).

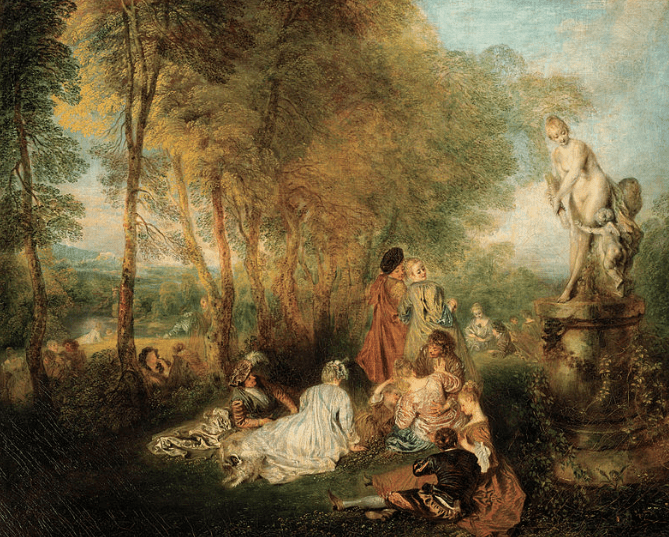

Second, the woman in the background is a mystery. The kind of wallpaper effect of the woman suggests Japanese art as a model. But Bourdieu argues that Manet likely had a work of “[Jean-Antoine] Watteau in mind” (maybe the Feast of Love, that woman in the righthand background) someone he admired a great deal. He puts this woman in as a “nod to Watteau … [that] closes the triangle of the three figures … She is treated differently: the brushstrokes are light, as in the style of Watteau” (71).

Luncheon on the Grass, Manet, 1863

The Judgment of Paris, Raimondi ca. 1510-1520

The Feast (or Festival) of Love, Watteau 1718-19

As Bourdieu finishes this “very strange exercise” he feels ashamed doing it, because he does not have the necessary competence. The problem is that those who do have the competence (art historians) don’t think of doing it and remain instead in the role of “interpreter, observer and analyst.” The question here is not a matter of “influence.” It is rather the HPist’s question that what painting the Luncheon was like for Manet gives no special insight into what was going on for Manet as he painted.

According to Bourdieu, what was going on for Manet was practice. This is particularly true because Manet was really never one to serve as Cartesian observer of his own interior process and usually gave boring, trite, cliche answers about his revolutionary work, including to Zola when Manet was doing his portrait. He seemed to be a zombie when he spoke about painting, but of course he was anything but a zombie. That in itself is data to the HPist, as it suggests a dimension of experience running so far past what we can access simply by recording verbalized beliefs about that experience.

At the end of this long examination, motivated by the art student who is despairing at the thought that his first-person experience may not have complete authority, Bourdieu finally gets around to answering him in the best way he can, with a kind of practical charity principle:

[Manet] was not entirely sure of what we wanted to do: he had a vague plan … And it was in the process of doing it that he found out what he wanted to do, as we do ourselves when we do something … To reply once again to the question put to me, which has caused me to slow down and fill out my argument: one can be very intelligent with one’s body, without using language, of course, when one is a dancer or pianist. Having said this, there is the particular problem of the executant as opposed to the person who produces his own text, or his own work of art. So there is an intelligence of the body … Painters know how to adopt towards painting a viewpoint that is a practical understanding; they have a practical perception which is based on know-how … they understand a savoir-faire as savoir-faire, and don’t write lectures on it (73)

References

Bourdieu, Pierre. (2017). Manet: A Symbolic Revolution. London: Polity.

Bourdieu, Pierre. (1996). The Rules of Art. Stanford: Stanford UP.

Dennett, Daniel. (1991). Consciousness Explained. Boston: Back Bay

Dennett, Daniel. (2003). “Who’s on first? Heterophenomenology explained.” Journal of Consciousness Studies 10: 19-30

Foglia, Lucia and Kevin O’Regan. (2016). “A New Imagery Debate: Enactive and Sensorimotor Accounts.” Review of Philosophy and Psychology 7: 181-196.

Pylyshyn, ZW. (2002). “Mental Imagery: In Search of a Theory.” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 25: 157-182.

Shepard, Roger and Jacqueline Melzer. (1971., “Mental rotation of three-dimensional objects” Science 171: 701–3.

You must be logged in to post a comment.