In a previous post, I addressed some issues in applying the property of “implicitness” to cultural kinds. There I made two points; first, unlike other ontological properties considered (e.g., concerning location or constitution), implicitness is a relational property. That is, when we say a cultural kind is implicit, we presume that there is a subject or a knower (as the second element in the relation) for whom this particular kind is implicit. Second, I pointed out that because of this, when we say a cultural-cognitive kind (mentally represented, learned, and internalized by people) is implicit, we don’t mean the same thing as when we say a non-cognitive (public, external, artifactual) kind is implicit. In particular, while implicitness is a core property of cultural-cognitive kinds (essential to making them the sort of cultural kinds they are), they are only incidental for public cultural kinds; that is to say the former cannot lose the property and remain the kinds they are, but the latter can.

One presumption of the previous discussion is that when we say that a cultural-cognitive kind is implicit, we are talking about some kind of unitary property. This is most certainly not the case (see Brownstein 2018: 15-19). In this post, I disaggregate the notion of “implicitness” for cultural-cognitive kinds, differentiating at least two broad types of claims we make when we say a given cultural-cognitive kind is implicit.

A-Implicitness

First, there is a line of work in which implicitness refers to the status of a cultural-cognitive kind as well-learned. As Payne and Gawronski (2010) note, researchers relying on this version of implicitness come out a tradition in cognitive psychology focusing on attention and skill acquisition (Shiffrin, R. M., & Schneider 1977, 1984; Schneider & Shiffrin 1977). The fundamental insight from this work is that any mental or cognitive skill can come, with repetition and practice, to be fully “automatized.” Initially, when learning a new skill or using a cultural-cognitive tool for the first time, it is likely that we rely on controlled processing. This type of processing is demanding of cognitive resources (e.g., attention), slow, and highly dependent on capacity-limited short-term memory. With practice, however, a cultural-cognitive kind may come to be used automatically; we can now use it while also having at our disposal the full panoply of attention and cognitive capacity related resources, such as short term memory.

Think of the experienced knitter who can weave a whole scarf while reading their favorite novel; contrast this to the beginner knitter who must devote all of their attention and cognitive resources into making a single stitch. In the experienced knitter case, knitting as a cultural-cognitive skill has become fully automatized (well-learned) and can be deployed without hogging central cognitive resources. This is certainly not the case in the beginner’s case. Standard cases discussed in the phenomenology of skill acquisition and in the anthropology of skill (e.g., H. Dreyfus 2004; Palsson 1994), fall in this version of “implicitness.” Chess or tennis playing becomes “implicit” for the skilled master or player in the Shiffrin-Schneider sense of going from an initially controlled to an automatic process (S. Dreyfus 2004).

As Payne and Gawronski (2010) note, this version of implicitness (hereafter a-implicitness) focuses the learning and cultural internalization process, isolating the relational property of acquired facility, or expertise (captured in the concept of automaticity) a given agent has gained with regard to the cultural-cognitive kind in question.

When transferred to such cultural-cognitive kinds as beliefs or attitudes, the a-implicitness criterion disaggregates into two sub-criteria. We may say of an attitude that is a-implicit if it (a) automatically activated or (b) once activated, applied or put to use in an efficient and non-resource demanding manner.

Thus, a stereotype for a category (filling in open slots in the schema with non-negotiable default) is a-implicit when its activation happens without much intervention (or control) on the part of the agent after exposure to a given environmental cue or prompt. A given stereotype may also be a-implicit in that, once activated, individuals cannot help but to use for purposes of categorization, inference, behavior, and so on. One thing that is not implied when ascribing a-implicitness is that agents are not aware of their using a cultural-cognitive kind in question. For instance, people may be very well aware that their using a default stereotype for a category (e.g., I feel this neighborhood is dangerous) even if this stereotype was automatically activated.

U-Implicitness

Another line work on implicitness comes out of cognitive psychological research on (long term) “implicit” memory. From this perspective, a given cultural-cognitive kind is implicit if people are unaware that it affects their current feelings, performances, and actions (Greenwald & Banaji 1995). In this type of implicitness (hereafter u-implicitness), a key criterion is introspective inaccessibility of a given cultural-cognitive entity.

This was clearly noted by Greenwald and Banaji (1995: 8) in their classic paper heralding the implicit measurement revolution, who defined implicit attitudes as “introspectively unidentified (or inaccurately identified) traces of past experience that mediate favorable or unfavorable feeling, thought, or action toward social objects.” While there is a link to the notion of a-implicitness in the mention of “traces of past experience” (which imply a previous history of internalization or enculturation) the key criterion for something being u-implicit is that people are not aware that a cultural-cognitive element is influencing their current cognitive, affective, and/or behavioral responses to a given object at the moment.

In the case of u-implicit cultural-cognitive entities, what exactly is it that people are not aware of? As Gawronski et al. (2006) note, there are at least three separate claims here. First, there is the idea that people are not aware of the sources of the cultural-cognitive kinds they have internalized. That is, something is u-implicit because the conditions under which they internalized it are not part of (autobiographical or episodic) memory, so people cannot tell you where their beliefs, attitudes, or other internalized cultural-cognitive entities “come from.”

Second, something can be u-implicit if people are not aware of the fact that a given cultural-cognitive kind (such as an implicit attitude) is “mediating” (or influencing) their current thoughts, feelings and actions. That is, a cultural-cognitive entity is “u-implicit” in the sense that people are not aware of its content. For instance, a person may implicitly associate obesity with a lack of competence, and this cultural-cognitive association may be automatically implicated in driving their judgments and actions toward fat people. However, when asked about it, people may be unable to report that such an attitude was driving their judgment. Instead people will provide report on the explicit attitudes that they do have content-awareness of, and this content will sometimes differ from the one that could be ascribed from the reactions and behaviors associated with the u-implicit cultural kind.

Finally, people may be content-aware that they have internalized a given cultural-cognitive entity (e.g., a schema or attitude) but not be aware (and in fact deny) that it controls or affects subsequent thoughts, feelings and actions; that is people may lack effects–awareness vis a vis a given internalized cultural-cognitive element.

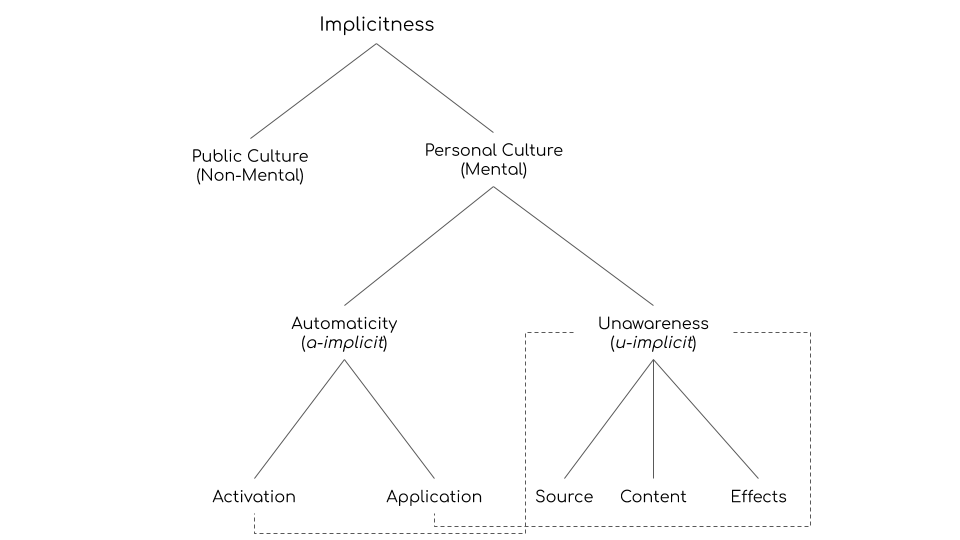

Figure 1. Varieties of Implicitness.

A branching diagram depicting the different types of implicitness discussed so far is shown in Figure 1 above. First, the notion of implicitness splits into two distinct properties, one applicable to public (non-mental) cultural kinds and the other applicable to cultural-cognitive kinds. Then this latter one splits into what I have referred to as a-implicitness and u-implicitness. A-implicitness, in turn, may refer to automaticity of activation or automaticity of application (or both) and u-implicitness may refer to unawareness of source (learning history), unawareness of the content of the cultural-cognitive kind itself when it is operating (e.g., an “unconscious attitude, belief, schema, etc.), or unawareness that the activation of this cultural-cognitive kind influences action.

Note that “unawareness” may also bleed into elements of a-implicitness (as noted by the dashed lines in the figure). For instance, a cultural-cognitive kind can become so automatic (in the well-learned sense) that people become unaware of its automatic activation or its application. The most robust way a cultural-cognitive entity can be implicit thus would combine elements of both a- and u-implicitness.

Implications

So, what sort of claim do we make of a cultural-cognitive kind when we say it is implicit? As we have seen, there is no unitary answer to this. On the one hand, we may mean that people have come to internalize the cultural kind (via multiple exposure, repetition, and practice) to the extent that they have acquired a relation of expertise and facility toward it. This is undoubtedly and least ambiguously the case for cultural-cognitive kinds recognize as (either bodily or mental) skillful habits. Thus, chess masters have an “implicit” ability to recognize chessboard patterns and produce a winning move, and expert piano players have an implicit ability to anticipate the finger movement that allows them to play the next note in the composition.

Note that while the typical examples of a-implicitness usually bring up expert performers, we are all “experts” at deploying and using mundane cultural-cognitive kinds acquired as part of our enculturation history, including categories (and stereotypes) used in everyday life, as well as ordinary skills such as walking, driving, or using a multiplication table. Once ensconced by practice, all of these cultural-cognitive elements have the potential to become “implicit” via proceduralization. In fact, it is the nature of habitual action to be a-implicit in the sense discussed both in terms of automatic activation by contextual environmental cues and of efficient (non-resource demanding) deployment once activated (unless it is overriden via deliberate, effortful pathways).

U-implicitness, on the other hand, is a stronger (and thus more controversial) claim. To say a cultural-cognitive kind is u-implicit is to say that it operates and affects our thoughts, feelings, and activities outside of awareness. Since the discovery of the unconscious in the 19th century and the popularization of the notion by Pierre Janet, Sigmund Freud, and followers in the 20th (Ellenberger 1970), the idea of something being both “mental” and “unconscious” has been controversial (Krickel 2018). The reason is that our (folk psychological) sense of something being mental implies that we are related to it in some way. For instance, we have beliefs, or possess a desire. It is unclear what sort of relation we have to something if we are not even aware of standing in any type of relation to it. But not all types of u-implicitness cut that deep. Among the varieties of u-implicitness, lack of content awareness is much more controversial than lack of source awareness, and when coupled with a lack of effects awareness, becomes even more controversial, especially when it come to issues of ascription and responsibility accounting.

For instance, we could all accept having forgotten (or never even committed to memory) the conditions (source) under which we learned or internalized a bunch of attitudes, preferences, and beliefs we hold for as long as we have awareness of the content of those attitudes, preferences and beliefs. What really throws people for a loop is the possibility they could have a ton of attitudes, preferences, and beliefs whose content they are not aware of and drive a lot of their behavior, thoughts, and feelings.

This is also a critical epistemic and analytic problem in socio-cultural theory featuring strong conceptions of the unconscious. In particular, the prospects of cultural-cognitive entities doing things “behind the back” of the social actor rears its ugly head. For instance, Talcott Parsons (1952) (infamously) suggested that “values” could be the sort of cultural-cognitive entity that was u-implicit (internalized in the Freudian sense), and which people had neither source nor content awareness of, putting him in the odd company of Marxist theorists which made similar claims concerning the internalization of ideology, such as Louis Althusser (DiTomaso 1982). Both proposals are seen as impugning the actor’s “agency” and committing the sin of “sociological reductionism.”

A more likely possibility is that a lot of internalized cultural-cognitive entities are not implicit in the full sense of combining both a and u-implicitness. Instead, most things are in-between. For instance, the “moral intuitions” emphasized by Jonathan Haidt (2001), can be a-implicit (automatically activated and automatically used to generate a moral judgments) without being (wholly) u-implicit. In particular, we may lack source awareness of our moral intuitions, but have both content (there’s a phenomenological or introspective “feeling” that we are experiencing with minimal content) and effects awareness (we know that this feeling is why we don’t want to put on Hitler’s t-shirt or eat the poop-shaped brownie). The same has been said for the operation of implicit attitudes and biases (Gawronski et al. 2006); they could be automatically activated and even used, and people could be very aware that they are in fact using them to generate (stereotypical) judgments, but, despite this content awareness, people may be in denial about the attitude driving their behavior (lack effects-awareness).

Habitus and Implicitness

In sociology and anthropology, various “implicit” cultural-cognitive elements are conceptualized using the lens of practice and habit theories, with Bourdieu’s theory of habitus providing the most influential linkage between cultural analysis in sociology and anthropology and research on implicit cognition in moral, social, and cognitive psychology (Vaisey 2009). The foregoing discussion highlights, however, that conceptions of implicitness in sociology and anthropology are too coarse for this linkage to be clean and that a more targeted and disaggregated strategy may be in order.

In the theory of habitus, for instance, Bourdieu emphasizes issues of learning, habituation, and expertise, which leads to the acquisition and internalization of a-implicit cultural-cognitive kinds; in fact the habitus can be thought of as a (self-organized, self-maintaining) system of such a-implicit kinds. This is especially the case when speaking of how actors acquire a “feel for the game,” or the set of skills, dispositions, and abilities allowing them to skillfully navigate social fields. In this case, it is not too controversial to emphasize the a-implicit status of a lot of habitual action and the a-implicit status of habitus as a whole.

However, when discussing how the theory of habitus helps explain phenomena usually covered under older Marxian theories of “ideology” and “consent” for institutionalized features of the social order, Bourdieu tends to emphasize features of implicitness coming closer to the u-implicit pole; that is, the fact that most of the time people do not have conscious access to the sources, content, and even effects of the u-implicit cultural-cognitive processes ensuring their unquestioning acquiescence to the social order (Burawoy 2012). This switch is not clean, and it is unlikely that the theory of implicitness that hovers around the “expertise” side of the issue (linking habitus to skillful action within fields) stands on the same conceptual ground as the one emphasizing unawareness and unconscious “consent” (Bouzanis and Kemp 2020).

While these issues are too complex to deal with here, the conceptual cautionary tale is that it is better to be explicit and granular about implicitness, especially when ascribing this property to a cultural-cognitive element as part of the explanation of how that element links to action.

References

Bouzanis, C., & Kemp, S. (2020). The two stories of the habitus/structure relation and the riddle of reflexivity: A meta‐theoretical reappraisal. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 50(1), 64–83.

Brownstein, M. (2018). The Implicit Mind: Cognitive Architecture, the Self, and Ethics. Oxford University Press.

Burawoy, M. (2012). The roots of domination: beyond Bourdieu and Gramsci. Sociology, 46(2), 187-206.

DiTomaso, N. (1982). “ Sociological Reductionism” From Parsons to Althusser: Linking Action and Structure in Social Theory. American Sociological Review, 14–28.

Dreyfus, H. L. (2005). Overcoming the Myth of the Mental: How Philosophers Can Profit from the Phenomenology of Everyday Expertise. Proceedings and Addresses of the American Philosophical Association, 79(2), 47–65.

Dreyfus, S. E. (2004). The Five-Stage Model of Adult Skill Acquisition. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 24(3), 177–181.

Ellenberger, H. F. (1970). The discovery of the unconscious. London: Allen Lane.

Gawronski, B., Hofmann, W., & Wilbur, C. J. (2006). Are “implicit” attitudes unconscious? Consciousness and Cognition, 15(3), 485–499.

Haidt, J. (2001). The emotional dog and its rational tail: a social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological review, 108(4), 814.

Krickel, B. (2018). Are the states underlying implicit biases unconscious? – A Neo-Freudian answer. Philosophical Psychology, 31(7), 1007–1026.

Pálsson, G. (1994). Enskilment at Sea. Man, 29(4), 901–927.

Parsons, T. (1952). The superego and the theory of social systems. Psychiatry, 15(1), 15–25.

Schneider, W., & Shiffrin, R. M. (1977). Controlled and automatic human information processing: I. Detection, search, and attention. Psychological Review, 84(1), 1.

Shiffrin, R. M., & Schneider, W. (1977). Controlled and automatic human information processing: II. Perceptual learning, automatic attending and a general theory. Psychological Review, 84(2), 127.

Shiffrin, R. M., & Schneider, W. (1984). Automatic and controlled processing revisited. Psychological Review, 91(2), 269–276.

Vaisey, S. (2009). Motivation and Justification: A Dual-Process Model of Culture in Action. American Journal of Sociology, 114(6), 1675–1715.

Pingback: Culture “Concepts” as Combination of Ontic Claims – Culture, Cognition, and Action (culturecog)

Pingback: Cultural Kinds, Natural Kinds, and the Muggle Constraint – Culture, Cognition, and Action (culturecog)